Shame

Directed By:

Steve McQueen

Written By:

Abi Morgan and Steve McQueen

Starring:

Michael Fassbender, Carey Muligan, James Badge Dale, Nicole Beharie, and Lucy

Walters.

Director of

Photography: Sean Bobbitt, Editor: Joe Walker, Production Designer: Judy Becker,

Original Music: Harry Escott

Rated: NC-17

for graphic sexual content and Michael Fassbender’s Fass-member.

Shame, the second feature from British artist Steve McQueen, opens on a

shot from top down on its main character, Brandon, sprawled naked across his

bed. But he only takes up half the frame, the other half highlighting his empty

grayish blue sheets. The painterly quality of this image is of course no

surprise to those who know Mr. McQueen, a conceptual artist that has only

recently moved into filmmaking. But it also highlights the emptiness that

surrounds Brandon; in a world where he can have anything, still finds himself

longing for something, anything, to fill the void of his life.

Mr. McQueen’s first film, Hunger, was an audaciously bold and

formalistically polarizing debut that followed the British IRA hunger strikes

in the late 1970s. Mr. McQueen, uninterested in politics, focused on the

control and degradation of the body, and the mental power to command such an organism.

It was also the first film to introduce us to Michael Fassbender, who went on

to starring roles in Fish Tank, Jane Eyre, A Dangerous Method,

and now plays Brandon in Shame. And if Hunger was about the

complete control of the body, Shame is about a body that constantly

feeds in order to keep the mental state from absolute disaster.

If you have

heard anything about Shame, you may know that Brandon is indeed a sex

addict (and that Mr. Fassbender reveals his manhood). The film, working from a script

by Mr. McQueen and Abi Morgan (The BBC Miniseries The Hour), paints a

much more abstract picture (to a bit to a fault) of Brandon than you may think.

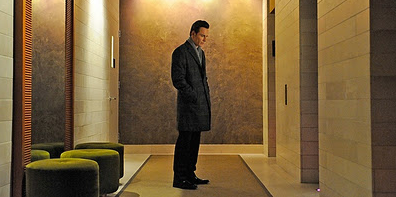

Brandon lives a high-class life up among the New York elite, working for what

seems to be some sort of finance company along with a playful and idiotic boss

(James Badge Dale). His apartment is a prism of sterility and his body

carefully kept together (the similarities to American Psycho pepper the

film throughout).

Except his sex life, which Brandon

can’t control at all. Masturbating in restroom stalls, thrusting into willing

women under a bridge, and stashing more pornography than a 13-year-old boy,

Brandon is uncontrollable when it comes to his libido, and impassible when it

comes to his ability to communicate. He goes on a date with a co-worker (Nicole

Beharie), which he almost blows by not being rude or cruel, but simply being a

stone cold slate of nothing. Mr. McQueen heightens the awkwardness by shooting

the whole take in a single long shot, never giving us a moment to breathe as

the man attempts to find any emotion inside. When the two later head to his

bedroom, Brandon can’t understand sex as an act of passion and romance more

than an act of relieving excess.

Much of this comes out in Mr.

Fassbender’s controlled and nuanced performance, which reveals the desire to

release furious anger but contained in a bottle much too small. Given little

dialogue, Mr. Fassbander uses the smallest of gestures to hint at Brandon’s

darker past and strange impulses. Like in Hunger, the thespian

understands performance is about physicality displaying emotion—-not through

giant movements, but miniscule suggestions.

The performance is in complete opposition at least to Carey

Mulligan, who plays Sissy, Brandon’s uncontrollable and unstable sister that

barges into Brandon’s life. Sissy, sporting a collection of vintage clothing

(as well as a couple hospital bracelets) lives in complete opposition to

Brandon’s outward life, throwing herself at anyone or anything willing to give

her some sort of connection. Their back-story is painted in the smallest of

details, most notably at a nightclub where she sings a mellowed version of “New

York, New York” and he lets out a single tear.

What has driven Sissy and Brandon

to their imperfect and destructive livelihoods? Mr. McQueen and Ms. Morgan kind

of leave the details to the visual clues, especially in how the director uses

the visual space and empty streets suggest a sort of hollow world of numerous

windows that let onto the world everyone’s secrets, but only in anonymous ways.

But these details are both where Mr. McQueen reveals his artistry as well as

his shortcomings. The director only uses the most minimal of dialogue to help

us understand Brandon and Sissy, but the actual things we learn are so slight

and lacking in nuance. The dangerous notions of Brandon’s culture that lead him

to his current life end up being much more simple than the intelligence of Mr.

McQueen’s camera often suggests. In Hunger, the director took a

well-known story and used an insider perspective to remark on details instead

of a whole picture. Here, Mr. McQueen lets the plotting of the narrative

sometimes get the best of him, which culminates in a series of obvious

sequences with an overbearing score. Shame

tries to bring Brandon’s story to Shakespearian heights, almost to the point of

parody with its cross-cutting and attempts to reach an emotional climax where the first half of the film carefully constructs a character study..

None of this would be too

frustrating if it weren’t for the restraint that Mr. McQueen often shows in

letting long takes capture feelings with authenticity, and using editing to

throw a wrench into our understanding. Shame presents a unique portrait

of a man searching for connection, but only understanding it through a physical

unstoppable force that is beyond his mental mechanisms. The film bookends

Brandon as he stares at a married woman (Lucy Walker) on the subway, all the

titillating possibilities running through his head as he stares up and down her

legs. But what could bring this man to think of her as more than an orifice, a

way to relieve himself of what ever keeps him awake at night, running through

the streets? Brandon can’t seem to figure it out, and Shame tries to

view the pains and terrible world of a man who's outer world remains a temple, while his inner self a monster constantly need of taming.

No comments:

Post a Comment